| Potoos Temporal range: Oligocene–Recent [1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Great Potoo with chick. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Superorder: | Strisores |

| Order: | Nyctibiiformes Informal[2] |

| Family: | Nyctibiidae Bonaparte, 1853 |

| Genus: | Nyctibius Vieillot, 1816 |

| File:Potoo range.png | |

| Global range (In red) | |

The potoos (POH-too) are a family, Nyctibiidae of Strisorean birds related to the nightjars, Oilbird, frogmouths and the swifts, hummingbirds and owlet-nightjars.[2] The seven extant species of potoos all belong to the genus Nyctibius (NIC-tih-BYE-us).[1][2]

These are nocturnal insectivores which lack the bristles around the mouth found in the true nightjars. They hunt from a perch like a shrike or flycatcher. During the day they perch upright on tree stumps, camouflaged to look like part of the stump. The single spotted egg is laid directly on the top of a stump.

Etymology[]

Nyctibius is from Greek νυκτιβιος nuktibios night-feeding < νυξ nux, νυκτος nuktos night; βιοω bioō to live.[3]

"Potoo" is originally from Jamaican English patoo; compare Twi patú owl.[4]

Victorian naturalists called them "tree-nighthawks", but the Creole "potoo" was originally used for only one of [seven] species, is now used for all of them.[5] They are sometimes called Poor-me-ones, after their haunting calls.[6]

Description[]

Highly cryptic chick resembles a clump of moss.

Potoos are medium-sized to large,[7] 41–50 cm (16–20 in), stoutly built,[5] with weak sexual dimorphism.[7] The wings are long and fairly pointed, the tail moderately long and the legs very short.[5] The toes are strong and flattened beneath and the soles of the feet are thickly padded and the toes have curved claws.[5]

All species are cryptically-coloured in greys or browns that resembles tree bark, while the Rufous Potoo is a cryptic shade of rufous.[7] Downy chicks are white, but in Rufous, Andean and White-winged, is not described.[7]

Common Potoo is identical to the Northern Potoo. They are best separated by voice and range.[7][8] In Costa Rica, where both occur, there appear to be no constant morphological characters to distinguish the two vocal types.[8]

Taxonomy[]

Paraprefica major fossil

The levels of genetic divergence among these species, however, may be the greatest in any single genus of birds,[1] and are equal to or greater than those typically found among birds in different genera or even families![1] This suggests that the species too are very old, once again hindering phylogenetic analyses.[1] It is possible that this genetic differentiation, although not obviously reflected in morphological differences, will be acknowledged in the future by separating the most divergent forms into distinct genera.[1]

Evolution and taxonomy[]

The potoos are today an exclusively New World family, but they apparently had a much more widespread distribution in the past. Fossil remains of potoos dating from the Oligocene and Eocene have been found in France and Germany.[9] A complete skeleton of the genus Paraprefica has been found in Messel, Germany. It had skull and leg features similar to those of modern potoos, suggesting that it may be an early close relative of the modern potoos. Because the only fossils other than these ancient ones that have been found are recent ones of extant species, it is unknown if the family once had a global distribution which has contracted or if the distribution of the family was originally restricted to the Old World and has shifted to the New World.

A 1996 study of the mitochondrial DNA of the potoos supported the monophyly of the family although it did not support the previous assumption that it was closely related to the oilbirds.[10] The study also found a great deal of genetic divergence between the species, suggesting that these species are themselves very old. The level of divergence is the highest of any genera of birds and is more typical of the divergence between genera or even families. This raises the possibility that there are several cryptic species to be discovered. For example the Northern Potoo was for a long time considered to be the same species as the Common Potoo, but the two species have now been separated on the basis of their calls. In spite of this there is no morphological way to separate the two species.[11]

Morphology[]

A Rufous Potoo showing eyeshine.

The potoos are a highly conservative family in appearance, with all the species closely resembling one another, and even species accounts in ornithological literature remark on the unusualness of their appearance.[11] Potoos range from 21–58 cm in length. They resemble upright sitting nightjars, a group they are closely related to. They also resemble the frogmouths of Australasia, but are stockier and have much heavier bills. They have proportionally large heads for their body size and long wings and tails. The large head is dominated by a massive broad bill and enormous eyes. In the treatment of the family in the Handbook of the Birds of the World, Cohn-Haft describes the potoos as little more than a flying mouth and eyes.[11] The bill, while large and broad, is also short, barely projecting past the face. It is also delicate, but has a unique "tooth" on the cutting edge of the upper mandible that may serve a function in foraging. Unlike the closely related nightjars the potoos lack rictal bristles around the mouth. The legs and feet are weak and used for perching only.

A camouflaged Andean Potoo.

The eyes are large, even larger than those of related nightbirds in the order Caprimulgiformes. As in many species of nocturnal birds, they reflect the light of torches.[12] These eyes, which could be conspicuous to potential predators during the day, have unusual slits in the lids.[13] The slits allow potoos to sense movement even when their eyes are completely closed. The plumage of potoos is cryptic and designed to help them blend into the branches on which they spend their days.

Habitat and distribution[]

The potoos have a Neotropical distribution.[11] They range from Mexico to Argentina, with the greatest diversity occurring in the Amazon Basin, which holds five species. They are found in every Central and South American country except Chile. They also occur on three Caribbean islands: Jamaica, Hispaniola and Tobago. The potoos are generally highly sedentary, although there are occasional reports of vagrants, particularly species that have travelled on ships. All species occur in humid forests, although a few species also occur in drier forests.

Behaviour[]

Lesser Potoo camouflaged on a stump

The potoos are highly nocturnal and generally will not fly during the day. They spend the day perched on branches with the eyes half closed. With their cryptic plumage they resemble stumps, and should they detect potential danger they will adopt a "freeze" position which even more closely resembles a broken branch.[14] The transition between perching and the freeze position is gradual and hardly perceptible to the observer.

Potoos feed at dusk and at night on flying insects.[11] Their typical foraging technique is to perch on a branch and occasionally fly out in the manner of a flycatcherTemplate:Disambiguation needed in order to snatch a passing insect. They will occasionally fly to vegetation to glean an insect off it before returning to their perch, but they will not attempt to obtain prey from the ground. Beetles form a large part of their diet, but they will also take moths, grasshoppers and termites. One Northern Potoo was found with a small bird in its stomach as well. Having caught an insect potoos will swallow it whole without beating or crushing it.

Potoos are monogamous breeders and both parents share responsibilities for incubating the egg and raising the chick. The family does not construct a nest of any kind, instead laying the single egg on a depression in a branch or at the top of a rotten stump. The egg is white with purple-brown spots. One parent, often the male, incubates the egg during the day, then the duties are shared during the night. Changeovers to relieve incubating parents and feed chicks are infrequent in order to minimise attention to the nest, as potoos are entirely reliant on camouflage to protect themselves and their nesting site from predators. The chick will hatch about one month after laying and the nestling phase is two month, a considerable length of time for a landbird. The plumage of nestling potoos is white and once they are too large to hide under their parents they will adopt the same freeze position as their parents, and resemble a clump of fungus.

Species[]

| Species of potoos in TiF order.[2] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Image | Range | Notes |

| Rufous Potoo, Nyctibius bracteatus |

|

Guianas to E. Peru.[7] Sedentary.[7] | Differs from the other potoos in morphology and vocalizations; could warrant a new genus.[7] |

| Great Potoo, Nyctibius grandis |

|

S. Mexico to S. Brazil.[7] Sedentary.[7] | |

| Long-tailed Potoo, Nyctibius aethereus |

|

Sedentary.[7] N. a. aethereus: north and east Brazil to northeast Argentina.[7] N. a. chocoensis: west Colombia.[7] |

|

| Common Potoo/Grey Potoo, Nyctibius griseus |

|

Sedentary.[7] N. g. griseus: Trinidad and Tobago, northern Argentina, and south Brazil.[7] N. g. panamanensis: east Nicaragua, southwest Costa Rica to west Ecuador.[7] |

Northern is identical and can only be separated by voice and range.[7] |

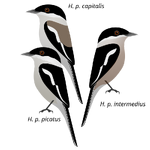

| Northern Potoo, Nyctibius jamaicensis |

|

Sedentary, but vagrant to Mona and Desecheo Islands (off Puerto Rico) and Cuba.[7] N. j. jamaicensis: Jamaica.[7] |

Common is identical and can only be separated by voice and range.[7] |

| Andean Potoo, Nyctibius maculosus |

|

||

| White-winged Potoo, Nyctibius leucopterus |

|

||

References[]

- ^ a b c d e f Cohn-Haft, M. (2016). Potoos (Nyctibiidae). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. (retrieved from http://www.hbw.com/node/52264 on 18 March 2016).

- ^ a b c d Boyd, John (2015). "nyctibiidae" (v. ed.). Retrieved March 18, 2016.

- ^ Jobling, J. (2015). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.), eds. "Nyctibius". Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. Retrieved 3-15-16. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ^ potoo. Dictionary.com. Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House, Inc. http://www.dictionary.com/browse/potoo (accessed: March 15, 2016).

- ^ a b c d Dr Perrins, Christopher; Dr Harrison, C.J.O. and Cameron, Ad (illu.) (1979). Birds: Their Life, Their Ways, Their World. Readers Digest Assn. ISBN 0895770652.

- ^ poor-me-one. Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/us/definition/american_english/poor-me-one (accessed March 19, 2016).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Cleere, Nigel (2010). Nightjars, Potoos, Frogmouths, Oilbird and Owlet-nightjars of the World. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691148571.

- ^ a b Cohn-Haft, M. (2016). Common Potoo (Nyctibius griseus). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. (retrieved from http://www.hbw.com/node/55156 on 19 March 2016).

- ^ Mayr, G (2005) "The Palaeogene Old World Potoo Paraprefica Mayr, 1999 (Aves, Nyctibiidae): its osteology and affinities to the New World Preficinae Olson, 1987" Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 3 (4): 359–370 doi:10.1017/S1477201905001653

- ^ Mariaux, Jean & Braun, Michael J. (1996): A Molecular Phylogenetic Survey of the Nightjars and Allies (Caprimulgiformes) with Special Emphasis on the Potoos (Nyctibiidae). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 6(2): 228–244. doi:10.1006/mpev.1996.0073

- ^ a b c d e Cohn-Haft, M (1999) "Family Nyctibiidae (Potoos)". in del Hoyo, J.; Elliot, A. & Sargatal, J. (editors). (1999). Handbook of the Birds of the World. Volume 5: Barn-Owls to Hummingbirds. Lynx Edicions. P.p. 288-297 ISBN 8487334253

- ^ Van Rossem, A (1927) "Eye Shine in Birds, with Notes on the Feeding Habits of Some Goatsuckers". The Condor 29 (1) 25-28

- ^ Borrero, J (1974) "Notes on the Structure of the Upper Eyelid of Potoos (Nyctibius)". The Condor 76 (2): 210-211

- ^ Perry, D (1979) "The Great Potoo in Costa Rica". The Condor 81 (3): 320-321

External links[]

- Potoo videos on the Internet Bird Collection

|

This article is part of Project Bird Orders, a All Birds project that aims to write comprehensive articles on each bird order, including made-up orders. |

|

This article is part of Project Bird Families, a All Birds project that aims to write comprehensive articles on each bird family, including made-up families. |

|

This article is part of Project Bird Genera, a All Birds project that aims to write comprehensive articles on each genus, including made-up genera. |

|

This article is part of Project Bird Taxonomy, a All Birds project that aims to write comprehensive articles on every order, family and other taxonomic rank related to birds. |

| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia (view authors). Please help by writing it in the style of All Birds Wiki! |